Weird Fiction Review: Poor Things

No animals were harmed in the writing of this review

Hello and welcome to the first official Weird Fiction Review of the novel Poor Things by Alasdair Gray. I’m glad you could make it!

In hindsight, I am not sure I could have made my task of reviewing harder for myself. I decided to review a novel that is both itself award-winning and the subject of an award-winning film adaptation. To add insult to injury, I saw the movie before I read the book. Was that silly? Maybe. I’m undecided about that still.

If you are interested in discussing views about how the film measures against the novel, please feel free to comment!

Nevertheless, I have attempted here to just stick with the most prominent themes I took away from the novel without delving into the merits of the film because, frankly, that would just complicate things.

Before I begin though, I just wanted to say thank you for reading—it really means a lot to me. If you like this post, or any of the others I have published before, feel free to ‘like’ it by clicking on the love heart in the ribbon at the top of this email (or if you’re reading it in the browser, the love heart at the bottom of the post). By liking, it just means that my posts might be seen by others who would enjoy reading it too.

Poor Things by Alasdair Gray

The work is not only the words on its pages

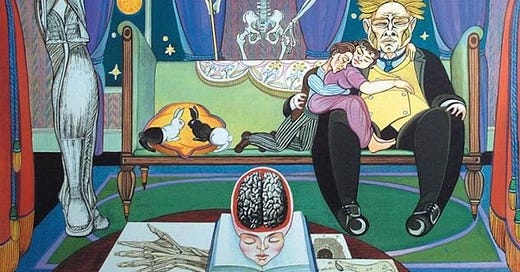

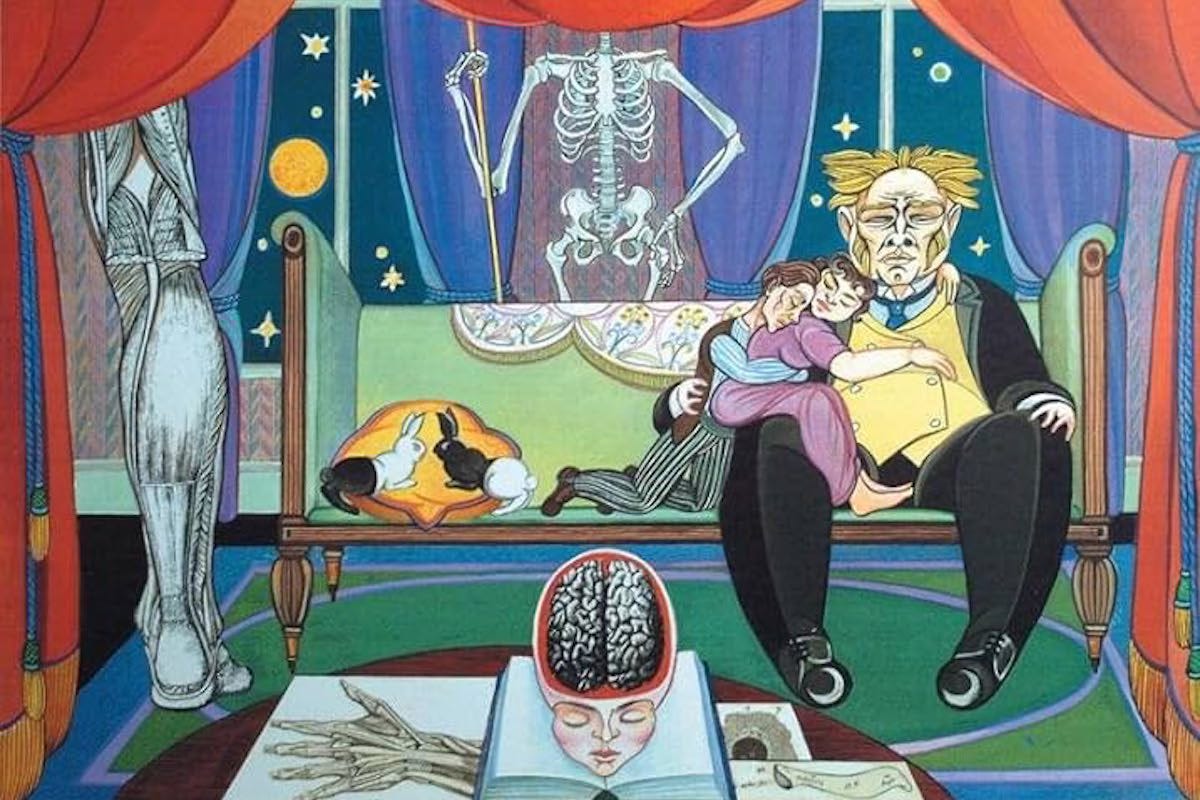

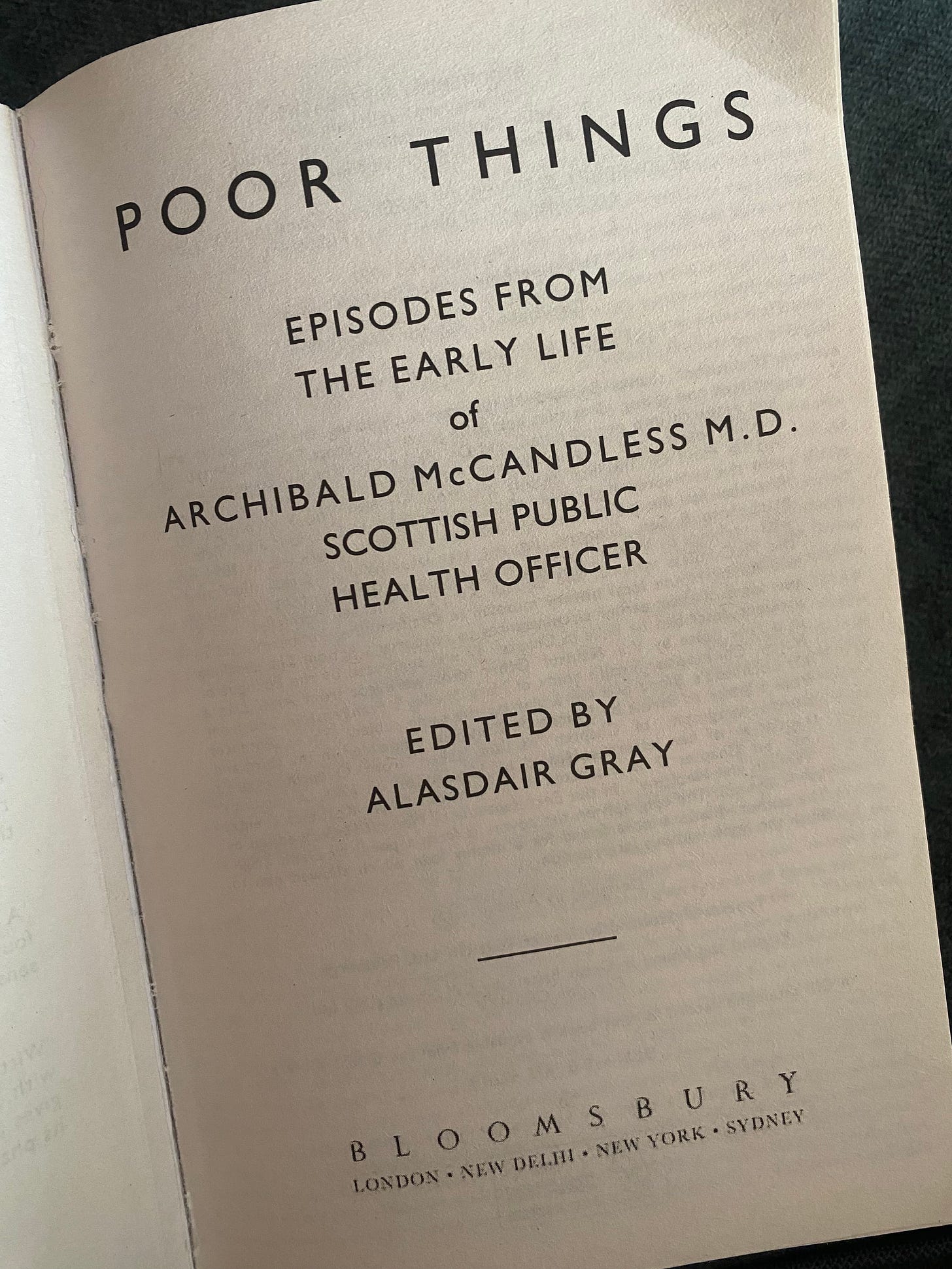

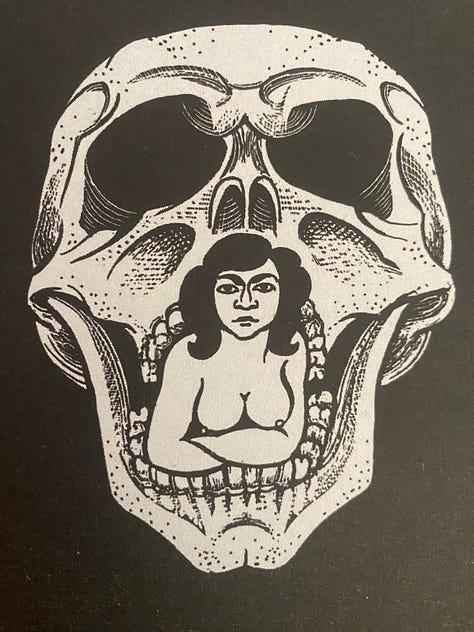

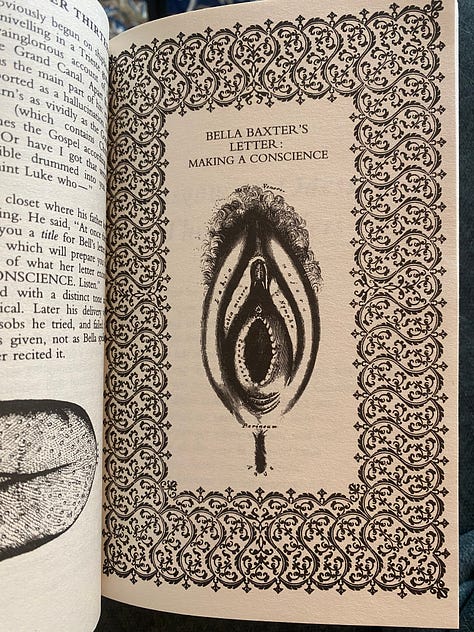

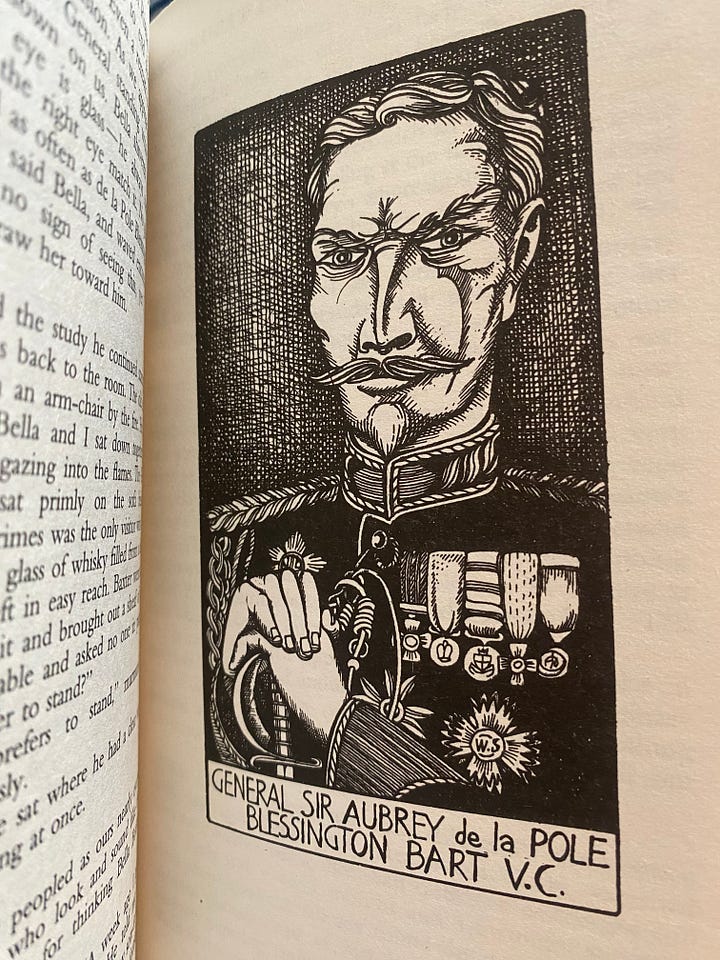

When I picked up Poor Things, the physicality and visual aspect of the novel itself gripped me. It has an excellent cover (seen above), a drawing by the author himself who was also an illustrator. As I fanned through the pages I found lots of black and white illustrations in the same style. Not only that but there were lots of different fonts used throughout to indicate different sections, voices, even a hand-scrawled letter. I was excited to encounter a book that seemed like an experience.

And boy did it live up to its impression. There are lots of words thrown around about Poor Things—19th Century gothic, feminist, political, satirical, metafictional—and they are all true.

One main thing to point out before we get started though is that Poor Things is structured as a novel within a novel, the “main” story of which is found in the second segment fictitiously written by 19th Century Glaswegian doctor Archibald McCandless M.D. and titled ‘Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D. Scottish Public Health Official’ (otherwise referred to here as the ‘Episodes’).

Creating or cannibalising

The reason Poor Things is a metafictional work comes from the fact that Alasdair Gray inserts himself into the novel. He introduces himself as the 'Editor’ of the manuscript for the Episodes which he tells us was given to him by local Glaswegian archivist Michael Donnelly sometime in the late 1980s, having saved it from ending up in landfill.

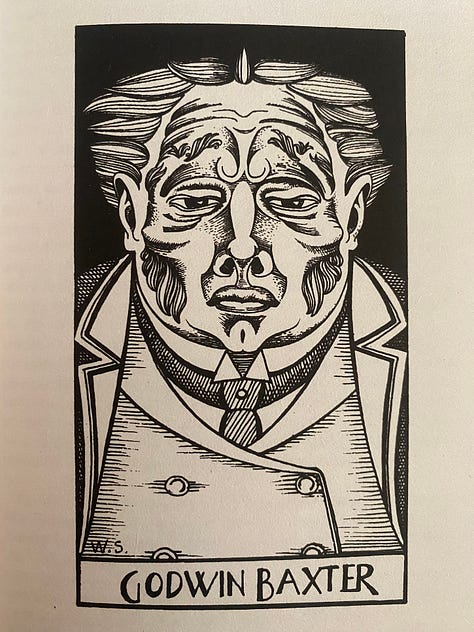

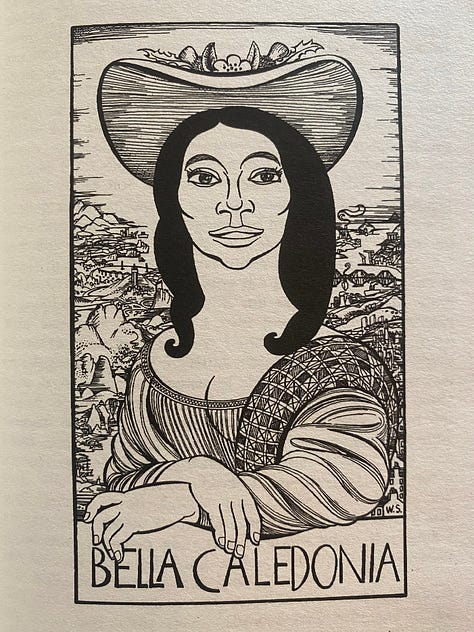

The Episodes, written by and told from the perspective of Archie McCandless, follows the tale of Bella Baxter who was created by Archie’s friend and surgeon extraordinaire Godwin Baxter from the drowned body of a 25 year old woman by inserting the brain of her unborn baby into her own cranium. Godwin yearns for a lover and companion in Bella, but instead becomes a father figure her, teaching her to be curious and kind which also sparks her interest in becoming a doctor herself.

Despite being a wealthy man whose father was a highly renowned physician himself, Godwin is largely shunned by society due to his Frankensteinian looks. According to Archie, Godwin is a grotesquely disfigured but gentle giant of a man whose body was experimented on by his own father. However, Godwin is the most compassionate and altruistic figure of the story precisely because he is ugly—he never wishes for anyone to be treated the way that he has been treated. Archie, by comparison, sometimes appears shallow and privileged, especially when he describes Godwin as having a voice so grating that he has to stuff his ears with cottonwool just to be able to have a conversation with him.

Gray the Author was heavily inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in concocting Poor Things. Like Frankenstein, there are many themes in this novel that are deeply rooted in the human experience—desire, power, societal expectations, reproductive rights, politics and religion, the subjectivity of truth and the prominence of certain voices over others.

In an exchange between the two after Godwin tells Archie the story of how Bella came to exist, Archie accuses Godwin of longing for (and creating for himself) what all men hopelessly yearn for: ‘the soul of an innocent, trusting dependent child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman’ (LOL).1 What Archie shows of his own ignorance is that Godwin’s motivations for ‘creating’ Bella do not lie in a desire for power over someone but rather a desire for connection to someone who will not view him as a monster because of how he looks, but rather to know and love him for his personality.

The antidote to born sexy yesterday

What is most interesting about these character dynamics is their use as a device for exploring feminist ideas of narrative told mostly through non-feminist perspectives. The Episodes written by Archie, when viewed from the perspective of the reader, are a complete parody of the ‘born sexy yesterday’ trope2 where Bella Baxter is very literally a child in a beautiful woman’s body and we watch as every man in Bella’s life tries to control her in some way.

However, Bella is anything but dependent on the men around her and resists their cynical influence. She loves Godwin as a daughter loves an encouraging and indulgent father, and Archie too for his gentility and mild manners. However, after promising that she will marry Archie, Bella soon absconds with scoundrel lawyer Duncan Wedderburn all over Europe and northern Africa, fearlessly seeking experiences before settling down with Archie.

One of the most notable aspects of Bella’s liberation in the Episodes is her experiences of conversation with those of different opinions and the pursuit of sexual pleasure. Unlike women, and even men, of her time, Bella is utterly uncontaminated by class-based hierarchy and decorum. She experiences pleasure and thoughtful conversation with a freedom that allows her to explore what feels good or is interesting, to challenge assumptions with curiosity and logic.

Bella, who keeps Godwin and Archie abreast of her travels through letters home, proves to be the most capable of them all of looking after herself, despite what they all perceive to be her childlike wonder at the world.

Bella’s narrative through her letters show that naïveté does not equal stupidity, but rather cynicism proves the undoing of our own curiosity towards the world around us and the limits of our imagination.

Bella proves that it is everyone else who deserve to be called poor things.

Truth is in the eye of the beholder

The genius of Alasdair Gray presents itself when the reader is given another account of events. McCandless’s Episodes is immediately contradicted by an accompanying letter from his wife Victoria (better known as Bella Baxter in the Episodes) written following the death of Archie.

Victoria’s reason for writing the letter is that clearly Archie had gone to a lot of trouble in getting the thing printed, with custom illustrations, and so it would be a shame to let it go to waste. However, she wishes to set the record straight that she is a plain, sensible woman, and says she does “not care what posterity thinks of it, as long as nobody now living connects it with ME” (emphasis original, p 251).

Not only does Victoria meticulously rebut each fantastical element of Archie’s outlandish story with logical explanations, but she reminds the reader of how Archie’s telling smacks of Victorian gothic literature with all its views of gender, patriarchy and politics. The tone of her letter is pragmatic and direct, a stark contrast to the romp of Archie’s Episodes and the wide-eyed charm of Bella.

The effect of including these different voices—Archie, Victoria, Gray the Editor—reveals that no one is ever really objective or reliable in their narration of events. Not only were the Episodes and Victoria’s letter written long after the events took place with the benefit of hindsight, but have also been editorialised with the opinions of someone who never knew them: Gray the Editor.

A memory for dialogue

Perception is the axiom on which this novel swivels back and forth. When I finished the novel, I kept returning to passages in the introduction and comparing how I had been led down one path by Gray and Archie, and up another by Victoria.

For example, Gray the Editor says in the introduction that he:

insisted on including [Victoria’s letter] as an epilogue to the book. Michael [the historian] would prefer it as an introduction, but if read before the main text it will prejudice readers against that. If read afterward we easily see it is the letter of a disturbed woman who wants to hide the truth about her start in life. (p. XIII)

However, Victoria had clearly written the letter with the intention that it be read first and against which wish Gray the Editor has acted. The hypocritical nature of suggesting that readers might be prejudiced by a particular order of reading, and then superimposing his conclusion as to whom to believe, reveals the very thing that Gray (the author) wants us to see: that all narrators are inherently unreliable.

This novel is an ouroboros

This book deserves to be read multiple times at different points in one’s life. There were so many subtleties throughout the novel that I am sure I will discover something new every time I read it.

I loved Poor Things for its wit, humour and wry satire, and I will be reading the rest of Gray’s work for a long time to come.

Page 36.

“"Born Sexy Yesterday" is a trope that describes a character, typically a woman, who is physically attractive yet portrayed as childlike or naive, often with a level of intelligence or maturity that contradicts her appearance or behavior. These characters typically lack real-world experience, creating a dynamic where their sexual appeal contrasts with their innocence and unfamiliarity with social norms.’ - source.